By AGRA Watch Intern Camille Munro

Civil society organizations and smallholder farmers around the world are boycotting the upcoming UN Food Systems Summit, which has privileged technocratic solutions and is poised to further consolidate corporate control over the food system–and over seeds. Already, four large multinational corporations–including Corteva (formerly DowDuPont), Bayer (formerly Bayer-Monsanto), and ChemChina (which owns Syngenta)–control over 70 percent of the world’s seeds. These monopolies not only pose serious and demonstrated threats to seed biodiversity, but also to food sovereignty.

Consolidation of seed companies, as of 2018 (Phil Howard)

There is perhaps no force that has been more damaging to farmers, peasants, and indigenous communities’ traditional seed systems than the 1991 UPOV convention–yet it is not widely understood by food sovereignty activists and organizations. Recognizing the need to understand and resist UPOV’s power, GRAIN recently published a report detailing the convention’s functions and implications, and is calling for a week of action in December 2021, to say NO TO UPOV!

What is UPOV?

The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) was established as a result of the first International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants in 1961. According to UPOV’s website, the organization’s mission is to “provide and promote an effective system of plant variety protection, with the aim of encouraging the development of new varieties of plants, for the benefit of society.” Its primary function since its inception has been the privatization of seeds and plant varieties. It achieves this privatization by codifying and granting intellectual property rights to plant “breeders,” or those who develop new plant varieties. Such breeders can apply for rights over a new seed variety in any UPOV member country. The rights conferred to the breeder are similar to those of copyright in the United States, in that they both protect the breeder’s financial interests in the variety while also recognizing achievement and labor in the plant breeding process. By providing this intellectual property protection, UPOV is intended to incentivize breeders to develop new plant varieties.

What’s wrong with UPOV?

Although UPOV claims to exist “for the benefit of society,” the convention favors commercial breeders over small-scale farmers and prioritizes private interests over public interests. Those who are typically recognized as “breeders” are large, international seed producers and agricultural corporations, making these the entities who usually acquire intellectual property rights under the UPOV system. There are also financial, definitional, and logistical issues within UPOV and in national seed patenting laws adhering to the convention that prevent those who are not backed by large corporations from obtaining breeders’ rights. The convention has allowed large companies and corporations to grant themselves rights to plant varieties, monopolize them, and prevent other people and communities from using the seed varieties freely.

While UPOV protects the interests of commercial seed producers, it provides no socioeconomic benefits whatsoever to peasants, indigenous communities, or small-scale farmers. In fact, UPOV is detrimental to them in a number of ways:

- UPOV allows commercial breeders and corporations to claim intellectual property rights over seeds that were developed through the age-old, collective work of indigenous communities, peasants and farmers. UPOV proponents claim that the convention does not allow for appropriation because rights can only be claimed for “new” varieties, but as the GRAIN report points out:

Every crop known today is the result of work varied out by a diversity of peoples over generations. It is a collective work, something akin to the collective character of the continuity of language. It is a collective conversation over millennia, in which people observe, select, practice multiple crossings, carry out field tests, and make selections (p. 5).

Although UPOV claims to grant intellectual property rights to breeders who “discover new varieties,” in reality they are allowing these entities to appropriate and privatize the fruits of others’ labor.

- Because UPOV allows commercial breeders to claim rights over peasant seeds considered “new” to the seed industry, people may be prevented from freely saving, exchanging, and selling their own seeds. Protecting, circulating, and providing access to seeds has been a common practice and a fundamental understanding in communities around the world, throughout history. Under UPOV, those wishing to use seed varieties may have to purchase them or pay a royalty to the company that claims the variety as its intellectual property. People who are found in violation of UPOV mandates may face fines, sanctions, or even imprisonment.

Although it is now widely accepted, UPOV initially faced widespread rejection by communities, organizations, agricultural entrepreneurs and even countries, because of how the convention converts public, communal, and culturally-significant plant resources into private property. By 1968, only 5 countries had ratified the convention, and at the time of the last revision in 1991, only 20 (primarily industrialized) countries were members. But in 1994, it became mandatory for every WTO member country to institute intellectual property rights for plant varieties; as a result, UPOV’s membership grew dramatically. Since this time, Western states have compelled non-industrialized countries to ratify the convention by including it in bilateral or regional trade agreements. The United States has included a clause obliging the other country/countries to ratify UPOV in every trade agreement the country has signed since 1991. As a result of these measures, 76 countries and 1 organization (the Africa Intellectual Property Organization) have ratified the convention today.

While UPOV proponents champion the convention as a force which encourages innovation and protects commercial interests, farmers around the world recognize that UPOV’s primary function has been to eliminate small-scale farming enterprises and foster dependence on expensive agricultural inputs from seed corporations. As the GRAIN report points out:

Today, the texts drafted by UPOV bureaucrats and industry representatives provide the ideological and legal backbone to all regulations and standards relating to seeds or “plant varieties” with a single script: eradicate, erode, or disable independent agriculture to subject it to the whims of large corporate farmers and seed and agricultural input companies. These corporations see independent agriculture as unwanted competition. That is why they criminalize peasant communities’ knowledge, techniques, and practices (pg. 4).

In sum, the UPOV system is an attack on the livelihoods of people and communities across the world and an attempt to entangle independent farmers in global capitalist agricultural systems. We must resist UPOV and demand that it be dismantled. We can do this by reframing the conversation and drawing attention to the ways in which UPOV is actually a threat to people’s rights, and by resisting free trade agreements that impose UPOV on non-industrialized countries.

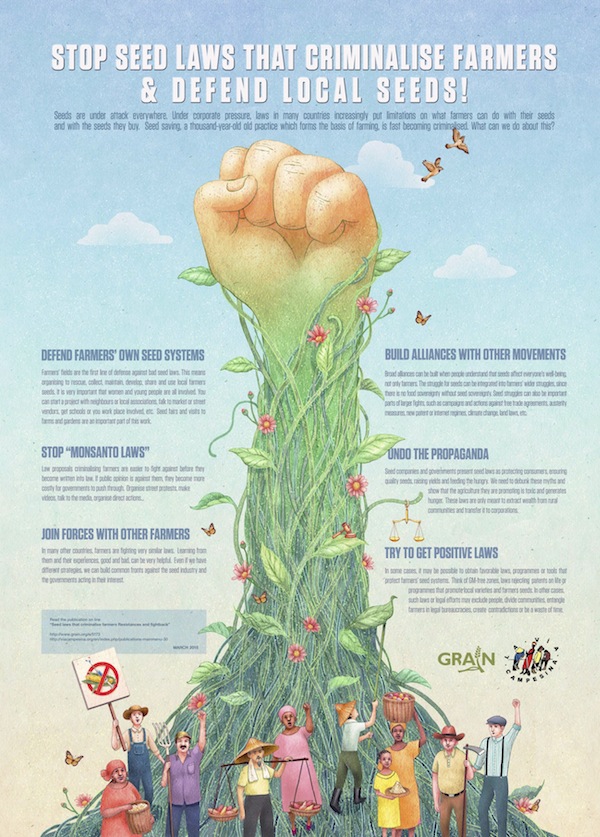

“Stop seed laws that criminalize farmers, and defend local seeds!” (GRAIN)

Activism against restrictive national seed laws based on the UPOV convention is widespread. In Ghana, for example, students and trade unions have mobilized alongside farmers, conducting public education campaigns and proposing public breeding programs as an alternative to breeders’ rights and intellectual property legislation. In Thailand, Costa Rica, and Mexico, among others, farmers, social movements, and environmentalists have fought free trade agreements with the United States which required adoption of UPOV, to varying degrees of success. And in July of this year, Nigerian civil society organizations protested a new Plant Varieties Protection Bill that would bring the country in compliance with UPOV (see addendum on the Nigerian protests, below).

Advocating for food sovereignty means advocating for seed sovereignty. It is crucial for food sovereignty advocates in the Global North to do what we can to support this important work, and to learn from the successes and failures of communities around the world who have mobilized to resist UPOV, breeders’ rights, and seed privatization. Resistance is crucial because, as the GRAIN report eloquently states: “UPOV is the ultimate expression of the war on peasants: resistance entails protecting their traditional system of saving, exchanging and multiplying seeds through channels of trust and responsibility.”

Addendum, Sept. 17: Over a hundred groups of farmers, youth and women representing Nigerian and African civil society recently compiled a petition denouncing the adoption of a UPOV91 based Plant Variety Protection law in Nigeria. The petition, which was written based on the notion that the UPOV Convention is designed “not for the interest of the African people but for nations with agricultural systems that are starkly different from ours where smallholder farmers are the mainstay,” can be accessed here.

Take action:

To join GRAIN’s actions against UPOV from December 2nd to 8th, follow this link: shorturl.at/abfoL and join https://web.facebook.com/groups/1247839988978502

Read the full call at: shorturl.at/abfoL

Related reading and resources:

Primer on UPOV 91 and Other Seed Laws

Seed laws around the world | EJAtlas

Intellectual property protection in plant varieties: A worldwide index (1961–2011)

The Role of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV)

UPOV to decide on farmers’ and civil society participation in its sessions